Iron

Year of discovery: 5000 BC

The main role of iron is to trap, carry and release oxygen. Most of the body's iron is found in two oxygen-carrying proteins - hemoglobin (a protein found in red blood cells) and myoglobin (found in muscle cells). Iron also serves as an enzyme cofactor in oxidation/reduction reactions (i.e., captures or donates electrons). These reactions are essential for cellular energy metabolism. Iron requirements change over the course of life. Iron requirements increase during menstruation, pregnancy and periods of rapid growth, such as childhood and adolescence.

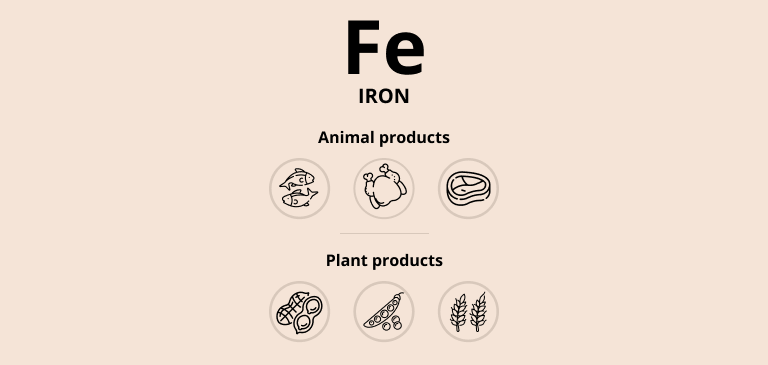

Main sources of iron

Red meat, fish, poultry, shellfish, eggs, legumes, cereals, dried fruits.

Bioavailability of iron

Iron levels are carefully regulated by the body, and the rate of absorption depends on the size of a person's iron stores. The more iron deficient a person is, the better the absorption rate will be in him. Conversely, in healthy individuals, iron absorption stops when iron stores are maximized. Many factors affect iron absorption. Heme iron from animal foods is absorbed on average twice as well as inorganic iron (from plant sources). The rate of absorption of inorganic iron also depends on the composition of the meal and the solubility of the particular form of iron. Factors that increase the absorption of inorganic iron are vitamin C and animal protein. Factors that inhibit the absorption of inorganic iron are phytates (found in grains), polyphenols (found in teas and red wine), vegetable protein and calcium (which also affects the absorption of heme iron). Food processing techniques that reduce the phytate content of plant-based foods, such as heat treatment, milling, soaking, fermentation and sprouting, improve the bioavailability of inorganic iron from such foods.

Risks associated with insufficient iron intake

Lack of dietary iron depletes iron stores in the liver, spleen and bone marrow. Severe depletion or depletion of iron stores can lead to iron deficiency anemia. At certain stages of life, a higher intake of iron is required, and if iron is not supplied to the body, the risk of iron deficiency will increase. Pregnancy, for example, requires additional iron to support extra blood volume in the body, ensure fetal growth and protect against blood loss during childbirth. Infants and young children need extra iron to support their rapid growth and brain development. Breast milk is low in iron. Therefore, infants fed exclusively on breast milk may also be at risk of iron deficiency. Rapid growth during adolescence also requires additional iron from the diet. Given the role that iron plays in energy metabolism, depletion of the body's iron stores can result in a decrease in the energy resources available in cells. Physical symptoms of iron deficiency include fatigue, weakness, headaches, apathy, susceptibility to infection and poor immunity in cold weather.